Image

Harnam Singh is the gentle giant standing back right in this group shot: Amar Singh is back left.

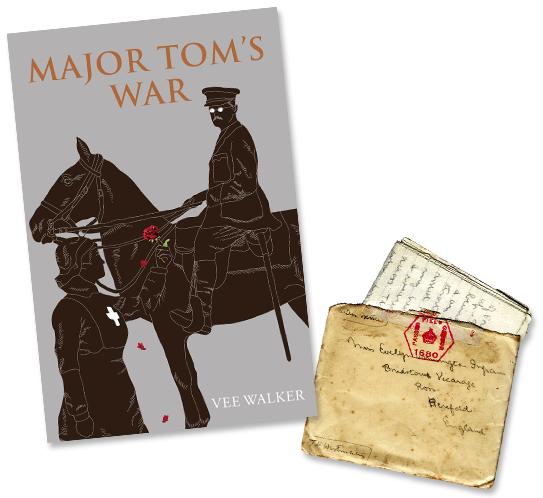

Unpublished Chapter

This chapter which does not appear in the published novel was intended to illuminate the reaction of the Indian Troops to their arrival in the south of France. It also introduces Harnam Singh, a Sikh officer who befriends Tom.

Breathing ice and fire

Marseilles, October 1914

Harnam Singh awoke at dawn on his forty-second birthday. He could not feel the tips of his fingers, nor his toes.

It was not that the Sikh risaldar had never felt cold before; more that he had never felt cold of this kind. It was glittering and sharp, all-pervading, inescapable. Every inhalation was ice, every exhalation fire, and he still watched in astonishment as his own out-breath left a cloud of visible mist hanging in the air. His lungs prickled with the simple effort of breathing.

And this in the south of a country where they would soon do battle in the far colder north!

He lay on his bed-roll beneath a blanket – two would have been better, but he was grateful for one – listening to the sounds of the men who still slept around him. Some snored with gusto; others coughed and sneezed with the feverish cold which already taken hold of heads and throats and chests throughout the regiment. It was partly for this reason that they found themselves still in Marseilles when others had already been moved north by train from the Saint-Charles station.

Harnam Singh and his men had been accommodated in a jumble of tents hastily erected in the elegant park named Bor-e-li, set on the fine lawns of a French Sahib’s palace. Another regiment, he knew, had been sent to a less refined but cosier old factory somewhere nearby. He had been glad to be under canvas at first, as he had found the journey from India most trying, sleeping in airless triple bunk beds down in the bowels of the ship. He had not been one of those who had feared crossing the Kala Pani, as he trusted in their leaders to see that they came to no harm; but since his arrival on French soil, he did indeed feel as though the cold and damp were seeping into his bones, sapping his energy. And now the frosts had come early.

The risaldar scratched his greying beard. They had not washed properly for a very long time and all of them longed to do so; providing the necessary equipment for many hundreds of men to perform their ablutions would not, he supposed, be very easy in this place. Some of the youngsters had braved the freezing waters of the fountain in the centre of the gardens but this had now been turned off, whether because of their antics and the watching ladies or the plummeting temperature he did not.

It did not occur to Harnam Singh to criticise those in authority over him, who had not, it appeared, thought through in sufficient detail the needs of this fine body of fighting men. At least there were decent latrines. They had also been promised new stout leather boots within a few days.

As he often did upon waking, before rising to say his prayers, Harnam Singh found himself mentally composing another letter to Birva Kaur his wife. He sorely missed her sweet voice and her savoury cooking. He told her that the food here was much better than on the ship – he could still smell the garlicky roasted goat on which they had been fed the previous night – but that he could not stomach the French bread they had been invited to taste with it: a long brown stick, hard on the teeth outside and pappy and tasteless inside. Some of the people who lived near the grounds where they were encamped would pass much nicer things to eat through the railings, candied nuts and other sweetmeats. This kept the men entertained and the process became rather like feeding buns to the elephants at the zoological gardens in Calcutta. The friendly French seemed to expect nothing in return.

One old lady in particular had visited several times, just, it seemed, to stare keenly at the Indian soldiers, which amused Harnam Singh very much. On the final occasion she beckoned him over and pushed a little parcel wrapped in brown paper into his surprised hands. Harnam Singh bowed his thanks and she went pink with pleasure, said something which sounded to him like ‘son-i- ton’ in her strange, fluid language, then shyly bustled away.

Inside the package he found a tiny figure of a Sikh just like himself holding a rifle, cleverly fashioned in painted plaster on a little green base. It would be his talisman, he decided, putting it into a pocket of his uniform against his heart, next to the faded photograph of Birva with their firstborn son.

Yes, thought Harnam Singh, if only the weather in France could be as warm as the welcome here.

He had written another letter in his head to his wife to pass the time in the ship, describing how he and his men slept stacked like hot chapattis in their stuffy bunks below decks, and how a friendly sailor had offered him a spare hammock instead; but he had found its swaying motion made his innards churn and he retreated to the cramped cabin.

Harnam Singh had liked it most up on deck in the fresh air, where he encouraged the men to exercise and keep limber as much as possible. He told Birva how a large fish had jumped from the sea to land, flapping and gaping, on the teak planks. He had grabbed it by the tail in his surprise and thrown it straight back into the sea again, while his men choked with laughter.

It was now one week since the arrival of the 38th King George’s Own in Marseilles and more regiments arrived by sea every few days. Soon there would be thousands in France, not mere hundreds. Harnam Singh had been distressed at the news before their departure that not even native officers would be permitted to bring their own mounts. He resigned himself to the idea in the certainty that his family would care for his trusted horses until his return, or if he failed to do so, his sons would then ride them. New chargers would be found for the cavalry when they reached the battlefields, he supposed. He hoped the horses would be good ones.

Harnam Singh had served in the Indian Army all his adult life and relished a fast ride and a just fight. He liked to imagine how he and his brothers would soon thunder down on the enemies of England in a cloud of hooves and flying manes and spurs with sabres aloft and a cry of ‘sat sri akal!’ He reached out instinctively to touch his gun. They had just been told that these treasured weapons would soon be replaced with more modern ones, and this thought made him uneasy. Better to fight with a weapon with which he was more familiar, surely? He stroked the polished gun-barrel with affection. They would have no choice in the matter, and that too he accepted without question.

When Harnam Singh had first marched his men off the ship at the docks in Marseilles two things had surprised them greatly. The first was that the solid land still appeared to be rising and falling under their feet as though they remained at sea. One young sowar was very sick and stumbled into another: he had to be hauled upwards and marched onwards with his arm linked through that of another fellow. This unsettling sensation gradually abated, much to the relief of all.

The second thing was the faces. In India one saw white skin too of course, but English people were in the minority, and those who lived there tended to darken over time. Here they were everywhere, hundreds upon hundreds of beautiful pale faces, men and women alike. They lined the roadsides, peered out of windows, even clung on to lamp-posts. Every face had a pair of hands attached and in most cases one of these hands was waving a white pocket-handkerchief, again in greeting. They were all smiling and cheering and shouting something which sounded like bona-ji, apparently a friendly greeting, which he encouraged his men to learn and repeat back to their hosts.

Harnam Singh liked the children in Marseilles most of all. His own two boys were almost fully grown, but these tiny ones still reminded him of their youthful days. French children resembled little princes and princesses in their ugly and tight apparel and yet still managed to dart this way and that like the little monkeys at home. One small girl escaped her ayah and rushed over to him from the crowd, clutching a flower of some kind in her chubby hand. The rubbery bloom was greenish with a pink tinge around the petals. He paused to salute her solemnly (which made her giggle and her ayah blush) and tuck it into a fold in his turban. Later one of the English soldiers he encountered told him it was called a hell-i-bore, blooming early; or a Christmas rose, to call it by another name. It looked like no rose Harnam Singh had ever seen; just one of many wonders to behold in France. As a skilled gardener himself, he marvelled at anyone who could coax a rose to bloom in such low temperatures.

Their French admirers soon realised how poorly prepared the Indian troops were for an unseasonably cold Marseilles in October. Most of the Indians had marched off the ship clad only in the thin cotton tunic-uniforms and sandals they had worn the day they marched onboard in Bombay. French winter garments of many different shapes and sizes began to rain down on them whenever they paraded, which was often. Initially Harnam Singh ordered his men to keep marching and ignore the offerings, but after the first few bitterly cold nights under canvas, he saw a risaldar-major ahead of him gather up a thick blue scarf, so he allowed the small lapse in discipline and did the same. The march that morning down the wide avenue lined with grand apartments which the French called a bool-i-vaar rapidly deteriorated into a free bazaar. He had accepted a shawl in bright green and gold, now twisted twice around his neck to keep out the chill. All the sleeping men were bedecked with other woollen garments; one lucky fellow, the envy of them all, lay warmly cocooned in an old fur coat he had turned inside out.

On the long dull journey by sea to the land they were to defend from invasion by Germany, there had been much discussion among his men over how best to gain izzat on the battlefield. Some youngsters proclaimed openly that they planned to martyr themselves at the first opportunity. Harnam Singh, older and wiser, pointed out that as the cause for which they fought was just, they would perhaps do better to stay alive and continue in the fray for longer.

He had shared his own decision with no-one other than Birva, deciding on his first day afloat on the Kala Pani that he would use his height and strength and cunning to protect a senior British officer whom he respected. He was not yet certain which of the Sahibs alongside whom he had worked in Calcutta would reappear in France. Most were honourable men who spoke Hindi and Urdu and other native languages as well as English. It would be his privilege to serve any of them, to the death if need be. Harnam Singh considered British rule of India to be both benign and enlightened as it had had prevented his own nation from fragmenting into a thousand warring princedoms. The great British Empire was still one worth defending.

He did not fear death; for what was the point? The One God who was the God of all religions already knew the appointed hour and day on which he and every man would die. It might be a death in battle, defending his officer, in which case the izzat would be great for his sons; who would soon, he hoped, be proud to follow their father into the Indian Cavalry. He might also prevent harm from befalling his chosen English officer, in which case he would live to enjoy the izzat with his family. All would yet become clear. He needed to be patient, and he would be guided on to the right path.

The sowar asleep to his right, little more than a boy, muttered something fearful and rolled over, shivering. Harnam Singh stood and stretched his long arms and back as much as he could in the tend, then placed his own blanket over the lad. He went outside to say his prayers, facing the watery sun as it rose. He ran up and down a pathway to warm himself, then stood and listened as a small, fat brown and red bird sang him a sweet song from a thorn-bush nearby.

In time, as the pale sun struggled to climb between grey clouds, Harnam Singh found he had completed his latest letter to his wife.

The letters would never be written or sent, of course, for his beloved Birva had died in childbirth when giving him his second son, more than fourteen years before.