Image

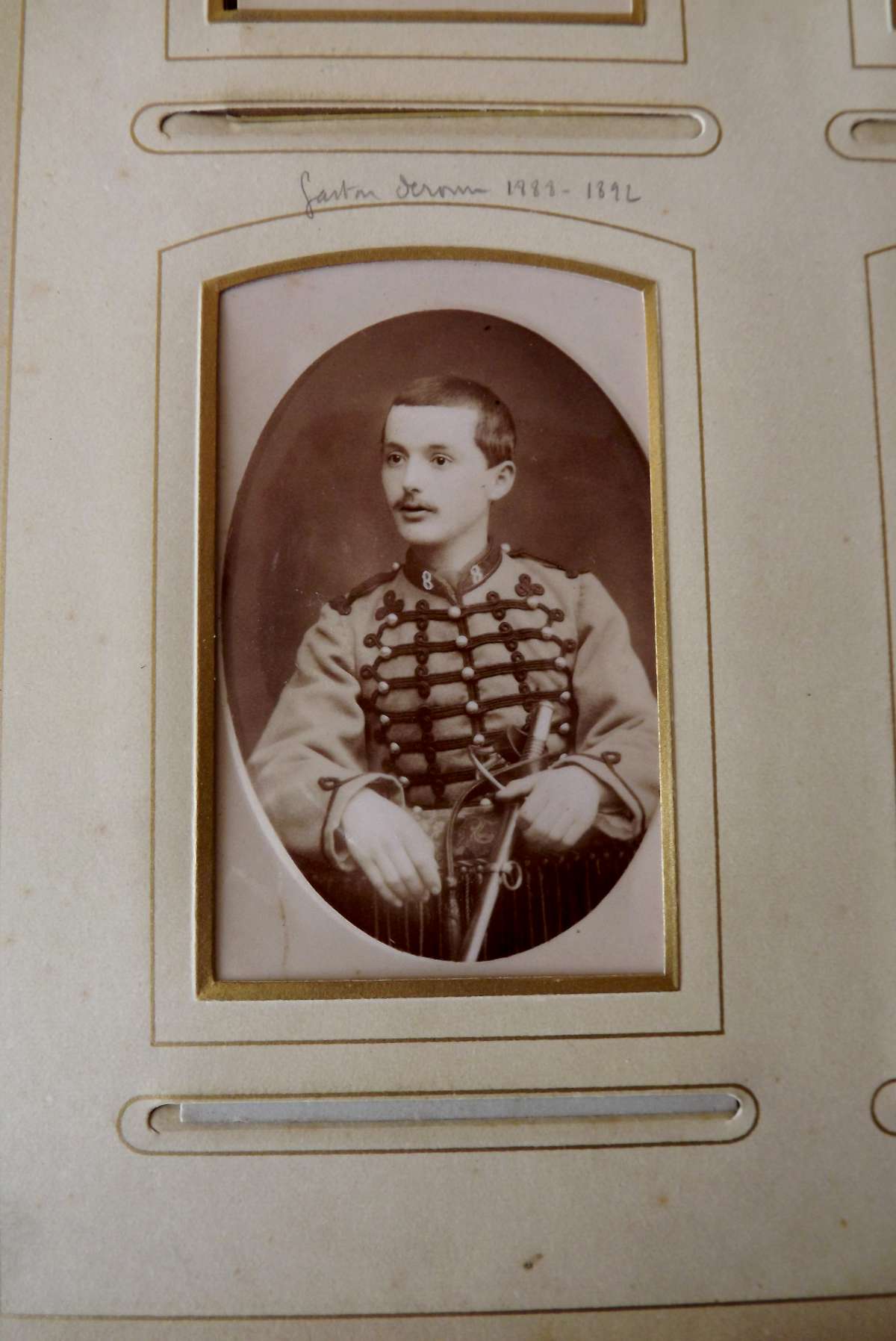

A charming picture of young Gaston, perhaps as an army cadet or about to undertake his military service. © Derome Family Archive

The Place

Bavay is marvellously real, a pretty little town with friendly inhabitants and a fabulous museum of Roman remains just on the French side of the border with Belgium. Go and visit it, they will be glad to see you.

The People

Père Duriez is invented, his name borrowed from my friend François, the town’s historian today, but must have existed. I thought I had invented Maître Corbeau until I discovered the real Jules Lebrun halfway through writing. The discovery of a photograph of him within the Derome family archives after I had finished the book was electrifying. He looks exactly as I imagined him, tall, hawk-nosed, austere, devout.

Not for the first time, I feel that the fates have helped me gather together what I needed for this book.

Fact and Fiction

In this scene I needed to establish why Gaston Derome was so opposed to the church in his youth. There are echoes here of the great Scots writer, folklorist and scientist Hugh Miller, who famously had fisticuffs with his schoolmaster before leaving to take up stonemasonry (you can visit his birthplace cottage on the Black Isle, it is owned by the National Trust for Scotland).

Early on, all the chapters had a little snippet of poetry and prose at the start but Bikram Singh Brar, my Kashi House editor, probably quite rightly, felt it would interrupt the flow of the book too much to leave them in. I did fight to retain the quotation from ‘Horatius’ at the beginning, though.

Gaston’s story, you may have noticed, is on its own timeline and does not follow the chronology of the rest of the book. Spreading Gaston chapters through the book was important to me: if I had respected the chronology there would have been ‘clumps’ of consecutive Gaston chapters which I wanted to avoid, in order to make his story more integrated.